Originally Written April 19, 2022

Blog

Why Is My Blood Sugar High in the Morning? What's Really Going On?

You did everything right before bed. Reasonable dinner, well-timed bolus, glucose steady at 130 mg/dl when you turned the lights off. And then you wake up at 260 mg/dl.

If you've been living with diabetes long enough, you've probably heard the explanation: the dawn phenomenon. Hormones rise in the early morning hours, your liver dumps glucose, and your blood sugar climbs before you even open your eyes. It's one of the most commonly cited causes of morning highs.

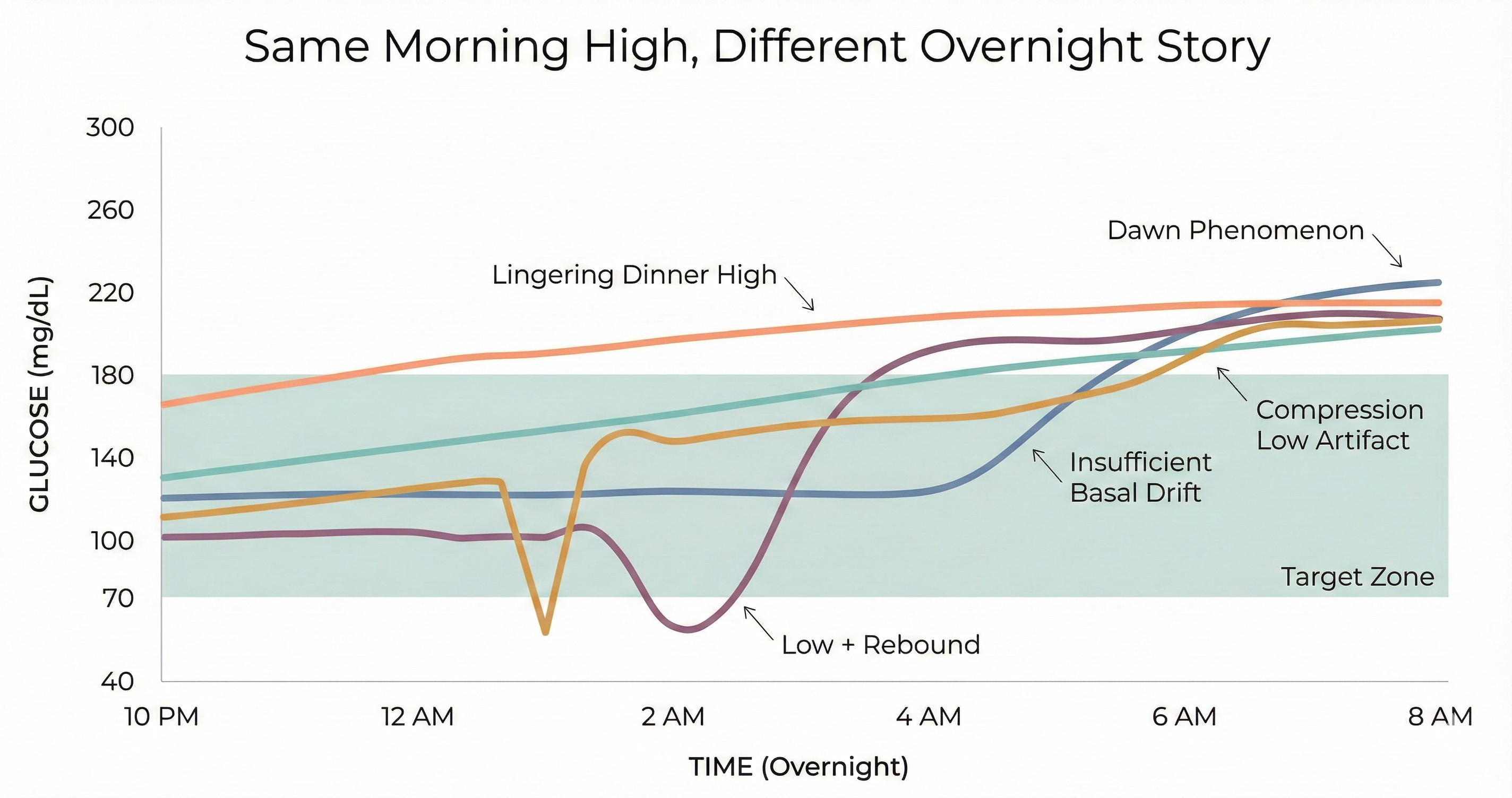

But here's the thing—the dawn phenomenon gets blamed for a lot of mornings it didn't cause. And if you're treating every high morning as a dawn phenomenon problem, you might be applying the wrong fix.

What actually happens to your glucose at night

Sleep should be the simplest part of managing diabetes. No food decisions. No activity spikes. Just basal insulin doing its job for seven or eight hours. In reality, overnight glucose is shaped by a surprising number of forces—and they don't all point in the same direction.

Lingering dinner highs. A meal that's still digesting when you go to bed doesn't stop affecting your glucose because you fell asleep. High-fat or high-protein meals can cause glucose to rise hours after eating, often peaking well into the overnight window. A 2017 study found that eating dinner at 9 PM versus 6 PM led to significantly higher overnight glucose exposure—even with the same food and the same insulin dose.

Insufficient basal coverage. Long-acting insulin provides a steady baseline, but "steady" doesn't always match what your body needs overnight. Insulin sensitivity shifts during the night. If your basal dose is tuned to avoid lows at 2 AM, it may not be enough to hold you at 6 AM. The American Diabetes Association notes that inadequate basal insulin is one of the most common—and most overlooked—causes of elevated morning glucose.

Rebound from lows. When blood sugar drops too low overnight, the body's counterregulatory response kicks in: the liver releases stored glucose to bring levels back up. The problem is that this rescue response doesn't have a precision dial. It can overshoot, sending glucose well above target by morning. For years, this was called the Somogyi effect. More recent CGM data has challenged whether post-hypoglycemic rebound is as common as once thought—a 2022 study of 2,600 patients found that morning glucose was actually lower after nights with hypoglycemia, not higher. But the experience of waking up high after a nighttime low is real enough that it deserves a closer look in your own data.

Compression lows and false alarms. If you sleep on the arm wearing your CGM sensor, pressure on the tissue can produce falsely low readings—what's known as a compression low. These aren't real hypoglycemic events, but they can trigger alarms, disrupt sleep, and lead to unnecessary carb corrections that genuinely raise glucose by morning. The telltale sign: a sudden, steep drop that resolves abruptly when you shift position.

And then there's the dawn phenomenon. Between roughly 4 and 8 AM, the body releases a surge of hormones—primarily growth hormone and cortisol—that increase insulin resistance and signal the liver to release glucose. This is a normal physiological process that happens in people without diabetes too. The difference is that a working pancreas compensates automatically with additional insulin. For someone on a fixed basal dose, there's no such adjustment.

Is the dawn phenomenon really the cause?

Probably less often than people think. A comprehensive review in Diabetes Care looking at 30 years of dawn phenomenon research found that its impact on overall glycemic control in Type 2 diabetes was modest—roughly 0.4% on A1C. And while studies estimate it affects around 50–55% of people with Type 1 diabetes, that still means nearly half of insulin users waking up high have something else going on entirely.

The bigger issue is attribution. Before CGM, there was no practical way to see what happened between midnight and 6 AM. You went to bed, you woke up, and whatever number greeted you in the morning was "the dawn phenomenon." We now have continuous data, and the picture is more complex. CGM traces can distinguish between glucose that was steady until 4 AM and then climbed (consistent with dawn phenomenon) and glucose that started rising at midnight because dinner was still digesting, or glucose that crashed at 2 AM and rebounded by morning.

As researchers at the ADA noted in 2020, combining CGM data with activity and meal timing makes it possible to distinguish true dawn phenomenon from these other overnight patterns. The label matters because the fix is different for each one.

How to read your own overnight data

If you wear a CGM, you already have the tool to figure out what's driving your morning numbers. Here's what to look for across two to three weeks of data:

Look at the shape, not just the endpoint. A morning reading of 200 tells you nothing about how you got there. Open your CGM app, filter for overnight, and trace the curve. A flat line that rises sharply after 4 AM looks very different from a slow climb that started at midnight—and they call for different responses.

Check for overnight lows. Even brief dips below 70 mg/dL can trigger a counterregulatory response. If you see a valley-then-peak pattern—glucose dropping and then climbing—the morning high may be a rebound, not a dawn phenomenon.

Note your dinner timing and composition. High-fat meals (pizza is the classic example) can raise glucose four to six hours after eating. If your overnight rise starts within a few hours of a late dinner, the food is the more likely explanation.

Look for compression artifacts. Sudden, steep drops that resolve abruptly—especially always at the same time of night—often indicate sensor compression rather than real hypoglycemia.

Compare weekdays and weekends. Different sleep schedules, meal timing, and activity levels create different overnight patterns. If your morning highs only appear on certain days, the cause is likely behavioral rather than hormonal.

The 2024 review in the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology confirmed what many CGM users have already discovered: nocturnal glucose events were significantly underestimated by traditional monitoring. Continuous data tells a more nuanced story—if you take the time to read it.

Why this matters

For many people with diabetes, nighttime is the most stressful part of management. A study in the Journal of Advanced Nursing found that 46% of adults with Type 1 diabetes reported poor sleep quality, with nocturnal glucose variability and fear of hypoglycemia as the primary drivers. Another 2025 review identified fear of nighttime lows as a key predictor of sleep quality across the diabetes population.

This isn't just a numbers problem. It's a sleep problem, a stress problem, and a quality-of-life problem. And it's made worse when every high morning gets the same generic explanation.

Understanding what's actually happening in your overnight data is the first step. The next is having the right tools to do something about it—whether that means adjusting your basal dose, changing your meal timing, or exploring automated insulin delivery that can respond to these patterns in real time, regardless of the cause.

Your nights don't have to be a guessing game.

References

- Bolli GB, et al. Thirty Years of Research on the Dawn Phenomenon. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(12):3860-3862. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Monnier L, et al. Analysis of prevalence, magnitude and timing of the dawn phenomenon. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2020. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Huang Y, et al. Confirmation of the Absence of Somogyi Effect in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2022. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Bolli GB, et al. Demonstration of a dawn phenomenon in normal human volunteers. Diabetes. 1984;33(12):1150-1153. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Martyn-Nemeth P, et al. Poor Sleep Quality is Associated with Nocturnal Glycemic Variability and Fear of Hypoglycemia. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2018;74(12):2849-2857. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Kulzer B, et al. Nocturnal Hypoglycemia in the Era of Continuous Glucose Monitoring. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2024. journals.sagepub.com

- Nishimura A, et al. Divided consumption of late-night-dinner improves glycemic excursions. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2017;129:206-212. sciencedirect.com

- American Diabetes Association. High Morning Blood Glucose. diabetes.org

- Abraham S, et al. Detecting Dawn Phenomenon in T1D with Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Activity Tracking. Diabetes. 2020;69(Suppl 1):891-P. diabetesjournals.org

- El Youssef J, et al. Fear of hypoglycemia: a key predictor of sleep quality among the diabetic population. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2025. frontiersin.org